When The Plan Goes To Hell

Everything was going according to plan. We'd go on a small road trip to the west coast, see family in Colombia, spend Christmas in South Florida, then live in Philippines to reduce our costs of living and maximize geoarbitrage before returning to the US to find a new monohull home.

Everything was going according to plan. I just returned from work abroad; we'd go on a small road trip to the west coast, see family in Colombia, spend Christmas in South Florida, then live in Philippines a little to reduce our costs of living and maximize geoarbitrage (earning money in one economy, and living in another) until July 2020 before returning to the US to find a new monohull home in order that we may start living aboard and sailing.

And then my dad died.

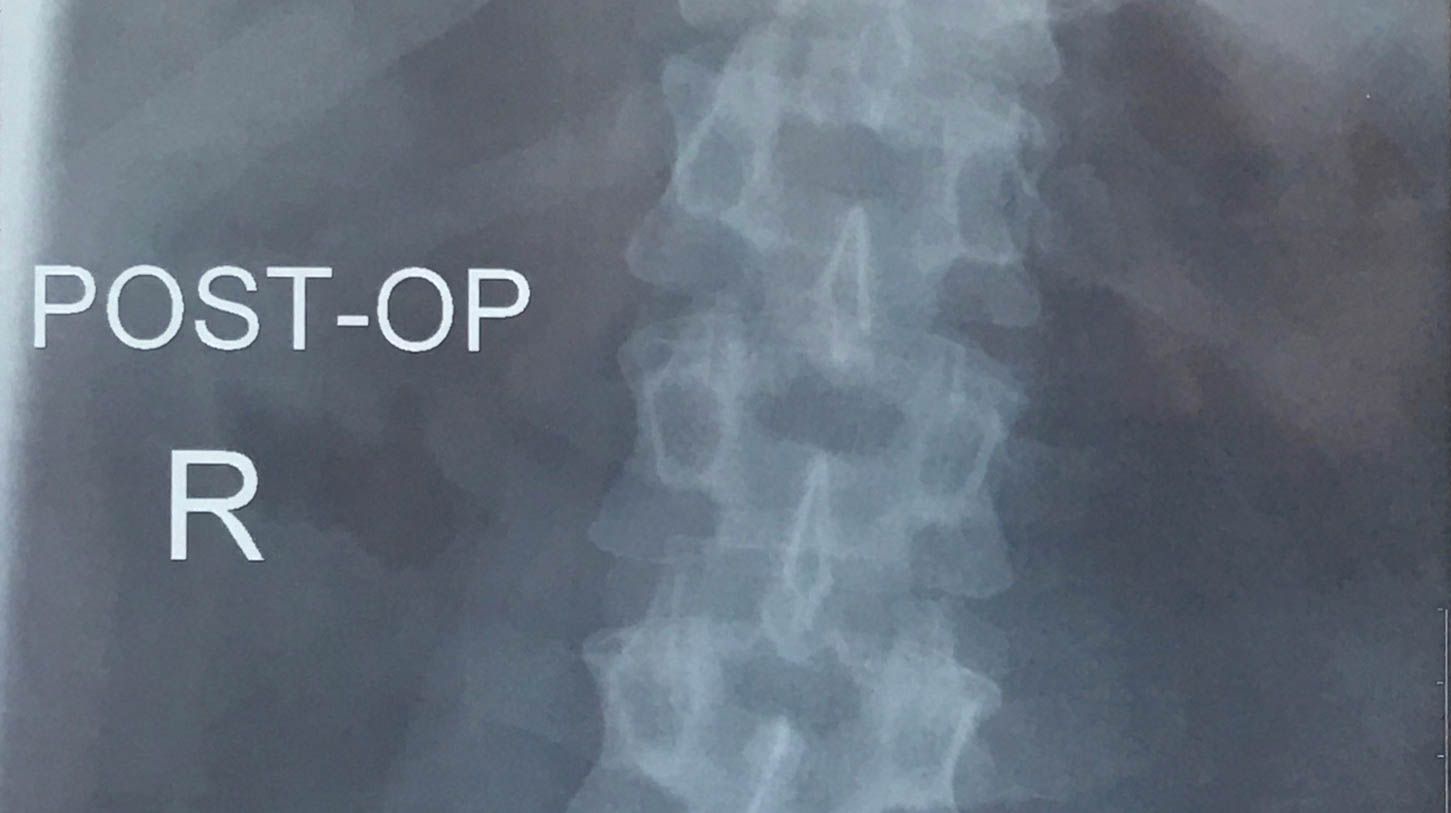

And then I required major surgery.

And then COVID-19 happened.

How planning ahead helped us cope with the rapid, and dramatic, changes in our world.

The First Turn of the Screw

At first, Shiela never wanted to consider failures. She wanted to ignore any failure outcomes and focus strictly on success. It's an honorable concept, but one that I feel leaves too much to chance. On the other hand, my parents, the Boy Scouts, and the US Military taught me to consider failure outcomes as well, and to plan contingencies for those. It took me a while to convince her that dwelling on failure and planning for failure are two wholly separate things. The former is foolish, the latter is prudent.

So, as a contingency, in 2017 we purchased a humble condo unit on the outskirts of Manila in Philippines. Ideally, we would make short-term rentals of the unit while away, and any time we needed a roof and a bed we would stay there. Including the costs of traveling there, we would save money overall. The main idea here is to always have a roof over our heads.

In October 2019, just after returning from work, my back started acting up and I was briefly hospitalized, having not been able to sit, stand, or walk. (As an aside, I'm talking about serious debilitating pain. Not like a backache. Not something one can just walk off. It's pain in the core of your body, from which there is no walking away; no reprieve, no escape save for unconsciousness. Pain enough that I plainly didn't even want to be awake.) After I returned home (with copious warnings from the doctors to seek emergency medical attention if I had trouble peeing – weird), I spent an afternoon arranging medical insurance for my back in Philippines –just in case– something happened.

We were all set.

Then my dad died.

The Complications Mount

In late February 2020, still a little weary from the loss of our patriarch, Shiela, the kids, and I turned up our chins and set off for the airport bound for The Philippines. Progress is only made by moving on.

Before we left, we became topically aware of some new SARS-like virus said to originate in China. It was becoming a common topic of discussion on the news but, as most learn about our current news reporting system, it's difficult to separate the wheat from the chaff from the first few news cycles. When we left the US, the administration continuously reassured the world that this new virus would "...miraculously go[es] away."

We arrived at NAIA in Manila, our temperatures checked before joining the queue for immigration, and once past all that we headed to the home of our extended Filipino family. We had a lot to do before I was supposed to return to the US in just two short months in order to sell our truck and for a little more work.

The Screw Tightens

It wasn't more than two weeks later, while I was shifting one of our little girls around in the bed so I could go to sleep, when I felt the familiar pang in my lower back reminding me to slow the fuck down. At the time, all this meant for me was about a week of discomfort, 800mg of ibuprofen once or twice a day for the duration, and promises to Shiela that I'd take it slow and reduce my body weight.

It was 8 March 2020. Everything else was still normal. Shops and restaurants were open, and taxis and ride-shares were still running; busses and jeepneys still packed to the brim. Shiela and I finished up our day; I prepared for bed and gingerly laid down, hoping for an improvement to the discomfort in my back the next day.

Now, I don't sleep as well as I'd like as it is, and in order to avoid having to slog across the room in the middle of the night to use the restroom, even though I just laid down, I struggled up and tip-toed to the toilet. I stood there, and tried to pee.

Nothing.

I had an urge. But nothing would come. "Okay", I thought to myself. Maybe I'm just having an off-day. This means I might just have to urinate in the middle of the night instead. Kind of a bummer, but whatever.

Tenderly, I make my way back towards the bed. Just three steps away, then two, one – then pain like a white phosphorus lance probes deep into my lower back, and I unceremoniously collapse onto the bed.

"Shiela, plan to go to the ER with me first thing in the morning. Let's get some sleep tonight. Tomorrow's going to be a long day." I tell her.

A State of Calamity

On 15 March 2020, with Shiela by my side and a mere two days after my surgery and still in the hospital, the Philippines starts locking down. The hospital in Bonifacio Global City is eager to get me out, as they're the first stop for most COVID-19 patients in Manila, and they don't want us to accidentally become infected.

To try and get transport home, Shiela goes to nearby car rental places, calls taxi companies, friends, even goods-moving companies (where I'd ride in the back like a sorry sack of rice through the now-deserted streets of Manila). Nothing is available. Everything is hard shut down, and nobody wants to risk going to jail, as that's the penalty for violating quarantine in Philippines.

We ultimately resort to hiring a private ambulance (which, mercifully, does not carry the same financial burdens like it does in the US) to get us back home.

They get us there. To our very affordable home, which we own outright, during a worldwide pandemic in which we're unable to travel for work even if I hadn't just had major surgery.

It's just as well. My doctors ordered me to a minimum of six months rehabilitation. Zero lifting or twisting. Minimize bending. Maximize walking and standing. So on day-1 home from hospital, I shuffled from my bed to the near window at the end of the hallway outside our unit, a mere 10 meters away. It took me five minutes, and from there I looked outside and enjoyed the first of 186 sunsets from our pandemic quarantine perch on the 11th floor of our building in Southeast Asia.

Luck is the residue of design.

–Branch Rickey

What's the point of all this?

In 2017 Shiela and I made a conscious choice to try and always ensure we have a roof over our heads, especially for our three children. It was our "just in case" for housing while we all galavant around the world for as long as our bodies (or patience) permit, and as a way to generate some passive income from rentals if they were vacant. In October 2019, just before leaving for our trip I pre-arranged medical insurance "just in case" something went wrong with my back. And the lessons I learned and the "just in case" contingencies I've created after the unexpected passing of my father, I hope, won't be needed for many decades.

I didn't envision the entire world being virtually unable to work; I just saved our own money and padded our own Emergency Fund in case we couldn't work. I didn't envision being quarantined in our 11th floor condo for six months on account of a worldwide pandemic, I bought it so we had an affordable place to live that was our own in case we couldn't work. I didn't envision needing a vertebral disc removal surgery in a foreign country, I arranged the medical insurance to pay my medical expenses – just in case.

Luck is the residue of design.

Design some luck into yours.